Hannibal & Gideon

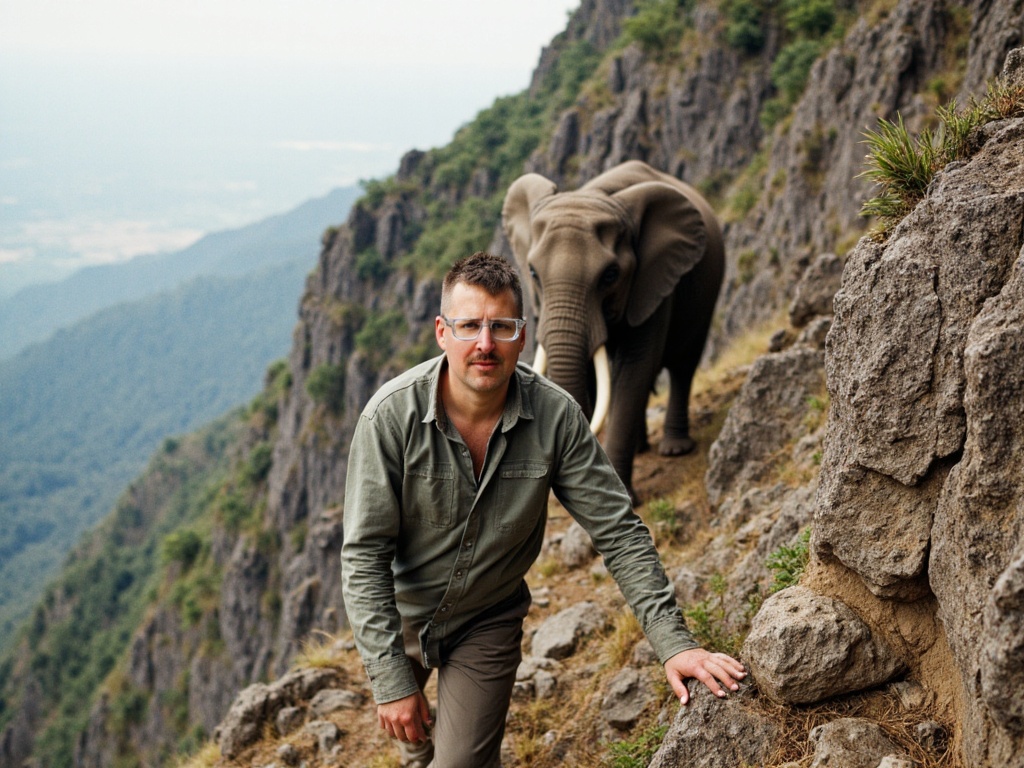

Maarten Inghels, artist and writer, sets out to follow in the footsteps of Hannibal Barca, who in 218 BC crossed the Alps with thirty-seven elephants to strike the Roman enemy from behind.

Scholars have debated for centuries which Alpine pass Hannibal took, and countless adventurers have sought to relive this mythical trek.

What drove these men to lead elephants into the mountains in the wake of the famed general? And is not adventure itself a privileged form of escape?

Picking up the elephant Gideon from the Lyon Zoo, Inghels embarks on the extraordinary crossing himself, blending imagination, history, and artistic vision along the way.

‘You’ll read this little book in one breath.’ – FRIESCH DAGBLAD

‘It’s a delight to walk alongside the writer and his animal, with reflections on the decline of the very notion of adventure in our time, vivid images and metaphors, humor, and playful asides.’ – ★ ★ ★ ★, NRC

‘An ode to misfits, to eternally young spirits in an adult world. With Hannibal & Gideon, Maarten Inghels has captured the adventure novel he has wanted to write since childhood.’ – ★ ★ ★ ★, HUMO

English sample translation (chapters 13–15) by Jonathan Reeder

13

Gideon places one foot alongside the other and for a moment I expect the ground beneath our feet to thud, but I don’t feel even a ripple.

Reluctantly, he takes another step and then turns his head towards me. The elephant looks at me and, at the same time, through me. I’m holding the black leash, whose loop hangs loosely around his neck. The strap is leather, but shackles are shackles. We still have to get to know each other. We’ve got plenty of time.

Gideon spent last night in the box trailer in the parking lot of the firehouse on the edge of Embrun, our starting point. He slept fitfully, it seems; the handler and the guard who have come with us heard the straw rustle. The handler from the safari park will stay with us until this afternoon, to give me a crash course in elephant first aid.

The Embrun fire department accompanies us that first day, and the gendarmerie, with a pair of police vehicles, tries to maintain order amid all the curiosity. The children at the primary school have been given the day off so they can join us; they’re wearing homemade elephant masks, a length of old bicycle inner tube for the trunk.

Dancers leap in circles around Gideon. A brass band plays, by turns, the national anthems of Italy, France and Belgium. The brass band will blow in our necks for the first few kilometers.

The director of the safari park wanted to hang huge posters along our route to inform the public of our journey, but I vetoed that. While I do want the world to be aware of my work, I can’t have yet more people getting in the way.

These days, an author is already sold to a book club, a podcast and a theater tour while their work is still no more than an embryonic idea, and I suspect that some reviews are written before the novel is even published, so I want to maintain the right to chew on my words alone for a while before letting them loose on the world.

Gideon and I are both nervous enough as it is, thanks in part to the posse of journalists in our wake. I see the elephant clap its ears forward, as though he’s trying to shield his eyes. Out of the corner of my eye I see a protester; I can just make out a placard with the words animal cruelty.

Sometimes a photographer or a cameraman shouts for us to look their way. Gideon continually shakes his head No. The agreement is that after today, the journalists will leave us in peace. From then on, I will send updates only to Safari de Peaugres, which will share my news items with the media.

We’re off, and right away I’ve broken into a sweat. I’m glad to finally be on the road, after months of sitting anxiously at home in the same country as the “master con man”.

I walk about ten meters ahead, the leash clamped in my sweaty hand. I look back at Gideon as often as possible, afraid of being trampled, until I get a cramp in my neck. His sour-sweet odor combines with the smell of the freshly mown hay in the fields and the traffic fumes.

Today we’ll walk uphill to a campground called La Place, eight kilometers outside the city. The police have instructed us to bypass the hypermodern N94 as much as possible, to avoid traffic jams and rubberneckers. It’s a pleasure to watch Gideon cross the bridge over the freeway and the second bridge across the Durance River, then turn left along a quieter local road to start the climb. The few oncoming cars slow down as they see our entourage approach. To our left is the valley, with the river and the ever-buzzing freeway; to our right, a thinly-wooded hillside. Every so often a car blares its horn as it passes us. I see some drivers rub their eyes in disbelief.

“You’re nuts, heh!” shouts one in French through the open window of his dilapidated Renault. “Tu as dû tomber sur la tête?!” It’s not clear whether he’s angry or just surprised, but either way he wonders if I’ve fallen on my head.

Gideon hardly reacts to the hubbub. As a main attraction at the safari park, he’s seen worse. Kids shouting and throwing soda cans at his head, aggressive fathers nudging him with the bumper of the car to get him to move, the veterinarian’s electric shock prod.

I’m reluctant to touch Gideon, afraid of being seen as unkind to animals, so I shrink back if he makes a move in my direction. I try not to force him, but rather to let him decide for himself to climb the mountain.

I dare say he’s in his element here. You can tell he’s not used to walking on asphalt, but he clearly enjoys the rock the same color as him and the children chanting his name. As for me, my nerves are shattered and I’m as pale as a dishrag, and I must take care not to be trampled by the swarming throng. The handler, terse but friendly, corrects my instructions to Gideon. Mainly, I have to learn to blow more forcefully on the guide whistle.

An elephant walks slowly and quickly at the same time. During a brief rest stop, I study his callused knee joint and the unique folds his legs are capable of forming. When he goes uphill, Gideon does so with a strange escalator-like motion.

Behind us, the foliage closes around the road and the last opening to the lowland.

Our route, from Embrun to Oulx in the hills above Turin, is eighty-one kilometers in total. My map shows a series of scrunched-up mountain ridges, like the lobes of a walnut, and in between these a river valley we’ll follow until we reach, after Montgenèvre, the long-awaited border crossing with Italy. Then we amble down the mountain to Oulx, where the truck will be waiting for us. The map reassures me that there are no extreme changes in elevation along our route.

I’m aiming for ten days for us to cross the Cottian Alps, but should unforeseen circumstances arise, we can stretch our stay in the mountains to two weeks. Then Gideon must definitely return to the safari park.

By late afternoon, a crowd has assembled at La Place campground. The resident campers, of course, but also the parents of the schoolchildren, a few police officers and the mayor of Embrun, who that morning had sent us on our way with a few pats on the shoulder. This, incidentally, is something we’ll encounter in every village: the mayor wanting a photo together with me and the elephant. And in every village I will have to refuse, ad nauseum, the local photographer’s request to climb onto Gideon’s back.

That evening I say goodbye to the handler, who drives back to Safari de Peaugres. He has confirmed that Gideon accepts me as his guide, and he’ll meet us at our destination, Oulx, with the transport vehicle. From there I’ll take the bus to Milan and then the international train home.

A tracker chip in the form of a keychain attached to the elephant’s ear allows the zoo to follow our progress. It’s a strange farewell. The handler makes me promise always to walk in front of the elephant.

14

It’s never quiet in the mountains. The birth of a small stone from a large one, the deafening wingbeat of a bee, the sniffing trunk of a sleeping elephant next to me.

Nor is the landscape bare. At six in the morning I oblige myself to leave my tent and admire the irresistible disorder of the larches and the limestone cliffs of the three-thousanders. The Durance at my feet marks the edge of the Massif des Écrins. In the distance, the houses of Embrun look like an overturned box of lego bricks.

I notice that I’m not yet quite at home in the wild. I hear a breaking branch behind me as a stranger turning the bolt of the front door and entering uninvited. Alarmed, I wheel around, but there’s nothing to see except for brush and the same fat pigeons as back home in the city. Further up, we’ll exchange the pigeon for the red-billed chough, and the rabbit for the marmot.

I could, here and now, relate the story of Hannibal: where he pitched his camp and which tribal elders he received in his tent; and then which alliance caused the Second Punic War to take a completely different turn, but those battles interest me less and less. It’s not the war injuries that fascinate me, but the muscle cramps of the spirit.

For me as a hannibalist, it’s about the virtually unthinkable journey of an elephant over a mountain. That small narrative element that piques our imagination. The absurd image of an animal that doesn’t really belong in this setting. It’s the same reason I embrace the surrealistic lunacy of Salvador Dalí taking his anteater for a walk in Paris.

I get up and clear away the remains of my breakfast. I want to get moving, so as to catch as much September daylight as possible before the sun dips behind the crest. The summer is on its last legs.

Gideon, who has slid his legs under his body to sleep, rightens himself, unfolding like a camping table. He rocks his head back and forth to have a look around. The handler said I mustn’t feel guilty about not hauling breakfast along for the elephant. Gideon’s appetite does not operate on a fixed schedule; rather, he forages his meals along the way, as he would do in the natural environment of his home country. At most, it’ll take some getting used to after the relatively monotonous diet of the zoo.

I load up my backpack calmly as possible. I don’t want to give Gideon the impression we’re doing something exceptional. He should feel at ease. For the third time today I check my phone’s weather app, the digital topographical map and messages from the home front, doing my best to hide my agitation from Gideon.

The morning is spent along the right-hand bank, on an asphalt road with relatively light traffic, until the Saint-Clément-sur-Durance bridge, where we cross over to the left bank. A busier N road crosses the river, and when we arrive there at lunchtime, it’s a nerve-wracking job to get Gideon safely across the line of cars.

Like a police cadet, I blow as loudly and self-assuredly as possible on my oversized whistle, the sign that he must move along. Luckily the elephant heeds my stop and start orders, and drivers slow down automatically when they see an animal as big as a house waiting at the crosswalk.

Most of the passengers get out of the car to witness the crossing. I have to exhort the drivers to cease their encouraging honking; it makes Gideon irritable. For the first time, I realize that Halliburton wasn’t exaggerating about the chaos that ensues when an elephant steps into the world of the automobile.

Once we’re across the bridge, the day’s main hazard is behind us. Following a wide, zigzagging road, we walk uphill to the fontaine pétrifiante, a pool of water underneath a waterfall adorned with glistening stalactites and gigantic beards of calcium. The blue-gray meltwater flows from the geriatric glaciers higher up the mountains.

I sit down on a large, water-cooled rock. My lunch consists of a block of cheese and what’s left of my fresh baguette. Gideon tugs the leaves off a few beech trees with his trunk, until it looks like autumn has kicked in early. Then he puffs and sniffs through the organic debris on the ground for anything edible. The trunk is a kind of industrial vacuum hose. His torso turns in small circles, his tail like a miniature brush or a far too short electrical cord.

I wonder if he’s enjoying himself. Does this feel like a break from the routine of the safari park?

High in the air, paragliders circle in endless loops and on the furthest hillside I can make out the wriggle of miniature figures. A chair lift glides above our heads; I don’t need to look up to know that the tourists in their white sneakers and idiotic flipflops are pointing at us.

Occasionally we encounter surprised hikers. They look at the elephant through their mobile phone cameras. I suspect they’re posting our location, because as the hours go by, more and more of them show up. Dozens of them at times, following us in single file. Sometimes I make obligatory small talk, but otherwise I do my best to focus on the elephant.

Richard Halliburton wrote that the enthusiasm of the locals was no less with his elephant Dolly than if she were a dinosaur. When the pair left Bourg-Saint-Pierre to embark on the steep climb through the alpine pass, more than five hundred people followed them.

Halliburton was right. I’m also walking through time with a dinosaur.

I rest my hand against the wet grotto wall and examine the slumbering stars in the rock. Once Gideon has sucked up a pool of water and left enormous footprints in the mud, we resume our journey.

This time I walk behind him, ignoring the handler’s orders. I have the feeling Gideon trusts me, and vice versa. The leash dangles indifferently around his neck like a loose necktie. I’ve never seen an elephant run, and I don’t think Gideon has any reason to bolt.

He seems to know the way: straight ahead. He is, I dare think, having a good time. The path pulls us upwards like a rope. His calf muscles show through his skin like steel cables.

For him, it’s easier to climb a mountain than a kitchen stepstool.

This is a bad metaphor, because of course he would immediately crush the stepstool, leaving nothing but an annoying splinter between his toes.

15

After noticing a crack in Gideon’s toenail when we set up camp that night, I take a photo of his foot and text it to the Safari de Peaugres. I’m suddenly quite worried about the possibility of it getting infected and the problems it could cause him. The safari park handler had put four boots in his carryall, just in case, to protect his soles against the granite floor of the mountain paths. But for these first few days, we’re still on the wooded hillsides and the paths are either asphalt or sand.

The director replies almost immediately that they were aware of this “chassis damage” and that I needn’t worry. The boots won’t be necessary yet. She wishes me a safe journey.

I resolve that in daylight I will make a thorough sketch of the landscape patterns on his skin.